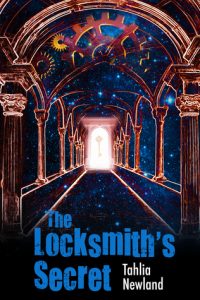

In The Locksmith’s Secret, Tahlia Newland has woven several narratives into a complex story about the joys and pitfalls of love and the enduring power of the imagination.

Writer Prunella Smith, whom readers may remember from Newland’s last book, Worlds Within Worlds, has found love with Jamie Claypole, an English transplant to Australia. The two are happy together, but Ella knows little about Jamie’s past. The gaps in her knowledge become apparent when Jamie is summoned home after his brother’s sudden death. All at once he becomes secretive about his family and where they live and how long he intends to stay with them.

The other narratives reiterate in various ways the problem Ella faces: whether to pursue Jamie and uncover his secrets or to reclaim the solitude she lost when he came to live with her.

Memories of unhappy past experience with a lover who abandoned her overshadow Ella’s hope for happiness with Jamie. Ella had been a ballerina with a promising career until a back injury forced her to give up ballet. Her lover, who was also her onstage partner, promptly discarded her once they could no longer dance together.

A Buddhist, Ella mediates regularly, and during meditation she’s transported into the world of Daniela, an Italian nun. On the brink of taking her final vows, Daniela finds herself attracted to the man who tends the nunnery’s garden. Like Ella, she faces an unexpected choice about the direction her life will take.

In addition, Ella has a recurring dream featuring a locksmith who may or may not be Jamie and who holds the secret to unlocking doors into countless other worlds, a metaphor for the creative and spiritual freedom that she seeks. She pursues the locksmith, but he seems always just out of reach.

Although troubled by Jamie’s secretiveness, Ella keeps writing fiction. Woven into The Lockman’s Secret is a steampunk novel that has taken hold of her imagination. The chapters appear as she writes them, and the story of intrepid reporter Nell and her efforts to uncover the villainy of Lord Burnett generates as much suspense as the main narrative. Like Ella, Nell values her independence and strives to prove her worth in the professional world. She worries that marriage to her employer’s son will mean the end of her career.

Newland interweaves all of these threads with consummate skill. Not once do they get tangled. Not once does the suspense flag, which is especially impressive in a contemplative novel like The Locksmith’s Secret. The credit goes to Newland’s mastery of narrative structure, to her concise and transparent prose that is eloquent without ever drawing attention to itself, and to her wonderfully varied and complex characters.

The worlds of Prunella Smith have a clarity and power that you won’t soon forget.