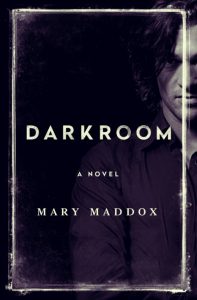

The Dangerous Darkroom tour is drawing to a close. If you hurry, there’s still time to enter the drawing for special prizes including a $25 gift card and autographed copies of Talion and Daemon Seer. Darkroom will also be on sale for $s0.99 through this coming weekend.

Meanwhile, I hope you’ll enjoy this brief excerpt from Darkroom. The story centers on assistant art curator Kelly Durrell’s search for her friend Day Randall, a talented bipolar photographer who mysteriously goes missing. This section relates how Day meets Gregory Tyson, the dangerous man who becomes her lover.

At the top of the stairs, Day stopped and listened to the voices. They boomed in the open space above the white geometric walls of the museum. The building’s shape molded the sound. A blind person could hear it and know the height of the ceiling and the steepness of its vault. Another kind of sight. But Day was all eyes. Give her scaffolding and she could shoot the maze of gallery walls, the sophisticated rats nibbling snacks and sipping chardonnay. Not her kind of shot, though. She was more the up-close-and-personal, whites-of-their-eyes, breath-to-breath type, going for that flicker of an instant before the lens fogged.

She kept standing there, breathing funny. She couldn’t be scared of those fools. Not her, the woman who’d flipped Baba and lived.

She’d felt sorry for one of his child whores and called the girl’s parents. He chased her through the house with a blade until she locked herself in the bathroom. He slammed the door, yelling that he would cut her throat, bleed her in the tub and carve her like a chicken, wrap the chunks in newspaper and toss them in a dumpster behind the supermarket with the other rotten meat. She was too scared to feel herself, like her body had turned into air. Baba had a way with threats. He might have carried them out except for Shawn, his half brother. Shawn calmed him down and told Day to get the fuck out, warning her that if she stuck her hook nose into their business again, he would personally waste her skinny ass and save Baba the trouble.

That was an occasion for terror. This was just a crowd of art snobs. No blades here. Just voices, diamond-sharp.

“Going to the party?”

Day whipped around, startled.

Stocky guy in jeans and a lumberjack shirt, not much taller than her. Dark hair streaked with gray. Life stamped in his face, deep impressions around his mouth and eyes. Irony in his smile but no trace of cruelty. He held out a gnarly hand. “Leonard Proud.”

She reached out with caution. Not that he seemed like the type who gave women crushing handshakes, but he looked strong. “Day Randall.”

His hand closed over hers—no squeeze or shake, but firm—and then let go. “Kelly says nice things about you,” he said.

“You’re her friend?”

“More like colleague. I’m on the board of the museum.”

She reached for the scuffed Pentax hanging from her neck, the first and only camera she’d owned, her longtime crutch and trusty third eye.

He waved his arm. “No.”

“It’s, like, official. Photos for the newsletter.”

“Even worse.” But he squared his shoulders and turned his face to stone. Ready for his close-up.

“Dude. I’m not a firing squad.”

Leonard clamped his mouth to keep the laughter in. His cheeks puffed a little and his eyes crinkled in amusement. She saw the moment and took the shot. Snap, snap. What she did best. Kelly would never use the photo in the newsletter—members of a board were supposed to look more dignified—but Day might add it to her portfolio if he agreed.

“Let me send you a print,” she said. “What’s your address?”

He gave her a business card, a plain one with a block font.

“You make Native American art? What kind?”

“Weaving and painting.”

“I’d like to see it.”

“There’s a couple of my pieces back there.” Leonard nodded toward the rear of the museum.

“Show me.”

“Some other time. I wanna get the meet-and-greet over with.”

Day followed him into a gallery of Inuit art. “Would you, like, do me a big favor? Point out the other board members so I’ll be sure and get shots of them. You and Joyce are the only ones I know.”

“How much is Joyce paying you?”

“She’s not.”

He snorted. “A new low, even for her.”

A glass case imprisoned several small totem animals carved from stone, including a curled-up seal so smooth and dark Day yearned to feel its coolness and weight in her hand. “It’s for Kelly. I mean, I’m not paying rent or anything, so I try to help.”

“You live with Kelly?”

“Yeah, for almost eight months. She’s in Chicago at a conference for curators, so I’m, like, helping her. It’s a surprise.”

Leonard raised his eyebrows. “You’re here without an invitation.”

“Do I need one?”

“Hell, no. You’re with me.”

Day followed him into the reception area, drafting in his wake like she sometimes drafted behind a semi in her Corolla to save fuel. She needed his forward energy to make her entry. She hated coming uninvited among these people wrapped in cashmere. Not hated—feared. You have to tell yourself the truth because these people are going to lie. Their smiles were rubbery, like masks.

Leonard veered toward the refreshments, tidbits of food on trays and glasses of wine lined up on the tablecloth beside them. Wine the color of pee after you drink way too much water. Day stopped. Too many people were crowded around the refreshments. She would catch Leonard after he got his food.

She felt something, turned, and caught Annie Laible staring from across the room. She smiled and waved and got a sour smile back. Annie had new and wilder hair, hennaed and spiked. Months ago, Day had asked permission to hang a few photographs for sale in her gallery—she needed money bad—and Annie had blown her off. Just a blunt “No” without saying why. Now it was like Annie still blamed her for asking.

Joyce was talking with two men in their forties. Older than Day, but not by much. Day was thirty-eight, though she tried hard to forget it. The short guy was wasted, face bright pink, eyes shining and empty. The other was tall and gaunt. His cheekbones drank the wind. She remembered the line from a poem she read growing up. She forgot what poem. Anyway, it described this guy. He turned his head as if he felt her stare. Their eyes met. Locked. She recognized him. Not personally. More like she was an alien species who finds another of her kind among strangers.

She lifted her camera, zoomed in, and took his picture. Then zoomed out and got the whole group. They were probably important if Joyce was talking to them.

He walked over to her. “You’re Day Randall. I bought two of your prints.”

Day knew which ones. Soon after she came to Boulder, she submitted her portfolio for an exhibit at the museum. Joyce turned down the portfolio but said she had a buyer for the prints at $350 each. A fortune for Day. Of course, Joyce never gave up the buyer’s name. She wouldn’t want Day selling to him and cutting her out of a commission. Now here he was, this guy whose cheekbones drank the wind.

“What’s your name?”

“My friends call me Gee.”

She grinned. “Am I your friend?”

“I don’t know. Are you?”

“I feel like we’re the only ones from another planet.”

Gee reached out and stroked her cheek. His fingertips set off a tingling that reached down to her core. “Let’s play Find the Magic.”

“What’s that?”

“This exhibit is called Magic and Realism.” He pointed to a painting. “What’s magical?”

The painting showed a bird and a cat, the tension between prey and predator. The bird’s beak was open in frozen song. The iridescent feathers, intense cobalt and silky green, burned into her mind. “It’s like a window into someone’s dream.”

“We’re doing analysis,” Gee said. “Notice how the details aren’t realistic. The color of the feathers, the way they glow. Not like any finch in the real world. And the proportions are skewed. The finch is ten times bigger than the cat. It fills the whole room.”

“But it’s afraid of the cat anyway.”

“How do you know?”

“I just do.”

“Maybe because the finch is hunched and the cat’s kind of batting at it. Check out these claws. The tips are red.”

“Yeah, like with blood.”

“Exactly.”

Day shook her head. “I don’t have to take things apart. I see them whole.”

“There’s nothing whole. Everything is pieces.” Gee’s gaze played over her face and started her tingling just like his fingertips had. “The universe blew up a long time ago.”

I called my publishing company

I called my publishing company