Most people would agree dead bodies are not a good thing. When one falls into your path, you step around or over it, or else you bury it with ceremony and weep. But there are a few enterprising folk who know how to make dead bodies work for them. One such creative entrepreneur is James Lewis, whose story is recounted by Joy Bergmann in her article “A Bitter Pill” in The Chicago Reader. Here’s a guy with oodles of initiative and imagination. He spots a dead body, and instead of thinking, “How sad!” or “Maybe I should call the police,” he asks himself three questions:

Does the dead body have money in the bank?

In 1978, Bergmann relates, the body of a Kansas City man named Raymond West was found dismembered in his attic. The body was too decomposed to determine a cause of death, but the cops soon learned Lewis had been lurking around the house after West’s disappearance and had cashed a $5000 check, supposedly signed by West. A business loan, Lewis insisted. Perfectly legitimate. After he was arrested, he told the cops the truth: Finding West dead in his home of natural causes, Lewis had done what any clever fellow would do — dismembered the body and hidden it in the attic, taped a note on the door so people would think West had gone on vacation, then helped himself to the checkbook. He was no killer! Only a scavenger.

For a while it seemed Lewis would be punished for showing some initiative, but he had an excellent attorney who glommed onto various procedural errors and argued eloquently:

“It’s one thing to kill somebody, it’s another to thing to dismember them after they’re dead. And while dismembering somebody after they’re dead is repulsive and repugnant, it’s not homicide” (qtd. in Bergmann).

Does the dead body scare the bejesus out of people?

In 1982 a wacko in Chicago bought several bottles of Tylenol, replaced the painkiller in some of the capsules with cyanide, and then replanted the bottles on various drugstore shelves. Some younger people might wonder how he put new plastic seals around the bottle caps. He didn’t have to. In those days bottles of over-the-counter medicine and vitamins were unsealed. After seven people died from taking the poisoned Tylenol capsules, that changed. We now have tamper-resistant packaging. James Lewis seized the opportunity to blackmail the company that made Tylenol, warning that more people would die unless he was paid a million dollars. Instead of being praised for trying to make lemonade from these unfortunate dead lemons, he was caught and sent to prison for extortion. Worse, the cops suspected him of being the wacko who did the poisoning. But they never made a case against him. Of course not. His only crime was trying to generate some income.

The Tylenol poisonings remain one of the major unsolved crimes of the last century.

Do people want to read about the dead body?

In this case, the answer seems to be no.

Several years ago Lewis published a novel about — what else? — mysterious poisonings that spread panic through a community. He promoted the novel on his Web site as part of a campaign to uncover the truth about the Tylenol poisonings in 1982. To date, the novel has three reviews on Amazon.com. One of them, written by Lewis himself, extols the novel and awards it five stars. The second reviewer titles his review “The Only Book I’d Burn” and the third declares that Lewis isn’t getting any of his money. I usually disapprove of reviews by people who haven’t read the book, but not this time.

If the FBI doesn’t finally nail James Lewis, I hope he ends up in a nursing home where the caretakers treat him callously, ignoring his complaints about the unbearable pain that never leaves him. “Bring me some fucking Tylenol!” he’ll scream. And the attendant outside in the corridor, slumped in her chair, will turn another page of People magazine.

Joy Bergmann’s article is worth reading: A Bitter Pill

In Albert Camus’ The

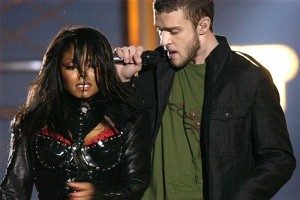

In Albert Camus’ The  Second-person point of view is necessary to this story. It models the way video affects how we look at ourselves, shapes our thinking. It implicates readers, whose reality has been shaped by video whether they know it or not. It reveals our collective obsession with recording and replaying. Remember Rodney King’s beating by the police and Janet Jackson’s “wardrobe malfunction” during a half-time performance at the Super Bowl? Video clips of these events were aired hundreds of times on TV. They have become part of our collective reality, or as DeLillo describes it, “the film that runs through your hotel brain under all the thoughts you know you are thinking.”

Second-person point of view is necessary to this story. It models the way video affects how we look at ourselves, shapes our thinking. It implicates readers, whose reality has been shaped by video whether they know it or not. It reveals our collective obsession with recording and replaying. Remember Rodney King’s beating by the police and Janet Jackson’s “wardrobe malfunction” during a half-time performance at the Super Bowl? Video clips of these events were aired hundreds of times on TV. They have become part of our collective reality, or as DeLillo describes it, “the film that runs through your hotel brain under all the thoughts you know you are thinking.”