Here’s a rerun of an old essay on use of the second person for new readers who missed it the first time around. I’m kind of proud of this one.

You don’t see much fiction in second-person point of view. You encounter plenty of characters who tell their own stories and all kinds of third-person narration, but only a few quirky narrators who address you the reader directly. Second person is unconventional and unexpected. Readers can be put off by its strangeness. There is also presumption in addressing readers directly, telling them what they they’re doing and thinking. The second person takes liberties, like a stranger who seizes your arm and tries to steer you where you hadn’t thought to go.

Sometimes it can be downright aggressive.

Point of view defines the relationship between the writer, the character, and the reader. In first person, a character speaks to the reader with the writer as an invisible medium. In the various modes of third person, the writer becomes visible and mediates between reader and character, creating a connection ranging from subjectivity that reveals every thought to the objectivity of a camera that shows only external action.

With second person this triangular relationship becomes complicated. While a third-person narrator is understood to be the author – or rather, a constructed version of the author – a second person narrator might be either the author’s persona or a character in the story, and might be speaking to the reader, to another character, or to itself.

In Albert Camus’ The Fall, the second-person perspective is unobtrusive in the beginning. The novel seems to be written in first person. The narrator, a former lawyer, speaks to an unnamed and silent listener. They meet in a bar in Amsterdam, and the narrator begins the story of his downfall. He continues the tale as they meet several more times over the next few days. It’s a story of lost innocence. Like Adam after the Fall, the narrator sees he is naked and understands that he — like every human being — is guilty. Several events contribute to the awakening. The most crucial happens while he is walking alone at night and sees a woman jump from a bridge. Rather than trying to rescue her or calling for help, he walks away.

In Albert Camus’ The Fall, the second-person perspective is unobtrusive in the beginning. The novel seems to be written in first person. The narrator, a former lawyer, speaks to an unnamed and silent listener. They meet in a bar in Amsterdam, and the narrator begins the story of his downfall. He continues the tale as they meet several more times over the next few days. It’s a story of lost innocence. Like Adam after the Fall, the narrator sees he is naked and understands that he — like every human being — is guilty. Several events contribute to the awakening. The most crucial happens while he is walking alone at night and sees a woman jump from a bridge. Rather than trying to rescue her or calling for help, he walks away.

The incident changes the narrator. He becomes self-conscious, a divided being: “My reflection was smiling in the mirror, but it seemed to me that my smile was double.” He looks at the world with new eyes. Although he is guilty, he is beyond judgment. No one is capable of judging him since they are equally guilty. Once an earnest believer in law, he rejects morality and the concept of justice. He explains to the listener:

If pimps and thieves were invariably sentenced, all decent people would get to thinking they themselves are constantly innocent . . . That’s what must be avoided above all. Otherwise everything would be just a joke.

At first the listener seems no more than a handy dramatic device. The narrator has to confess to someone. But it slowly becomes clear that the listener is part of the story; he is implicated. The narrator admits to stealing a valuable painting, and the listener could expose him. But he won’t. He sees himself in the narrator, just as readers do. The second person in The Fall includes not only the listener, but everyone. We’re all guilty.

In his short story “Videotape,” Don DeLillo uses second person narration directly. The story has no I, only you. The narrator is watching a video clip on the news. Filmed accidentally by a child, the clip shows a man being shot in his car by someone called the Texas Highway Killer. The narrator is obsessed with the clip and wants to watch it every time it appears on a news show. And he watches himself play out the obsession the way he would watch himself on video. He becomes an image of himself, objectified and placed in a framework for analysis:

You keep on looking because things combine to hold you fast – a sense of the random, the amateurish, the accidental, the impending.

His thoughts stretch beyond his small obsession to reach the understanding that video has radically changed reality for him and everyone else in our culture. Even the killer’s modus operandi is inspired by video.

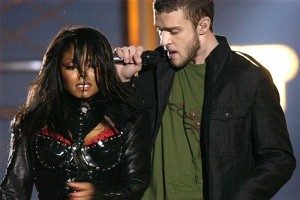

Second-person point of view is necessary to this story. It models the way video affects how we look at ourselves, shapes our thinking. It implicates readers, whose reality has been shaped by video whether they know it or not. It reveals our collective obsession with recording and replaying. Remember Rodney King’s beating by the police and Janet Jackson’s “wardrobe malfunction” during a half-time performance at the Super Bowl? Video clips of these events were aired hundreds of times on TV. They have become part of our collective reality, or as DeLillo describes it, “the film that runs through your hotel brain under all the thoughts you know you are thinking.”

Second-person point of view is necessary to this story. It models the way video affects how we look at ourselves, shapes our thinking. It implicates readers, whose reality has been shaped by video whether they know it or not. It reveals our collective obsession with recording and replaying. Remember Rodney King’s beating by the police and Janet Jackson’s “wardrobe malfunction” during a half-time performance at the Super Bowl? Video clips of these events were aired hundreds of times on TV. They have become part of our collective reality, or as DeLillo describes it, “the film that runs through your hotel brain under all the thoughts you know you are thinking.”

From these two examples, second person seems to be a technique for literary masters, but it’s available to any writer who cares to give it a shot. I wrote a section of my thriller Talion in second-person and present tense. A girl is enduring torture at the hands of a sadistic killer. I wanted the narrative to feel intense and immediate. First-person failed to convey the shattered state of a character whose personality is being destroyed along with her body and who struggles to hold onto a fragment of her personality.

I’m presumptuous, talking about my writing along with that of masters like DeLillo and Camus, as if I’m anywhere near their league. I write genre fiction, but I try to learn from the best. What matters is whether the technique works. If second person were wrong for the section, it would be a distraction. Apparently it’s not. Though a few readers have criticized Talion for its occasional shifts into present tense – something they think shouldn’t be done in genre fiction – no one seems to have noticed the second-person narration. Maybe the descriptions of torture are so harrowing that readers don’t notice she and her have become you and your and they’ve joined the victim beneath the killer’s knife.

As with any literary technique, second person works best when it has both a narrative and thematic purpose. Ideally, writers don’t up and decide to write in second person; they have a story that can’t be written any other way.

Jax finds himself torn between his father’s idealism, as revealed in the journal he left, and the hard pragmatism and ambition of Clay and Gemma. His ambivalence about the club’s criminal enterprises drives much of the conflict within the family. There are echoes of Hamlet, with Jax as the brooding son and Clay as the uncle who has taken his dead brother’s wife. Gemma, however, is no foolish Queen Gertrude. She’s more like Lady Macbeth without the guilt.

Jax finds himself torn between his father’s idealism, as revealed in the journal he left, and the hard pragmatism and ambition of Clay and Gemma. His ambivalence about the club’s criminal enterprises drives much of the conflict within the family. There are echoes of Hamlet, with Jax as the brooding son and Clay as the uncle who has taken his dead brother’s wife. Gemma, however, is no foolish Queen Gertrude. She’s more like Lady Macbeth without the guilt. When Jax marries his childhood sweetheart, Tara (Maggie Siff), Gemma’s connection to her son is threatened. A skilled surgeon, Tara stitches up the Sons’ gunshot wounds and learns to shoot a gun, but she doesn’t want the outlaw life for their children. She urges Jax to abandon the Sons. He also wants something better, but his loyalty to the club and lack of middle-class job skills keep him from walking away. After Clay cedes the presidency to him, he tries to move Sons out of gunrunning and into pornography, a less violent business, but various forces work against against him. Tenuous alliances with other gangs and with the IRA suppliers depend on the continued arms trade. Feuds with other gangs and various federal investigations require his immediate attention. And both Gemma and Clay want things to remain as they are.

When Jax marries his childhood sweetheart, Tara (Maggie Siff), Gemma’s connection to her son is threatened. A skilled surgeon, Tara stitches up the Sons’ gunshot wounds and learns to shoot a gun, but she doesn’t want the outlaw life for their children. She urges Jax to abandon the Sons. He also wants something better, but his loyalty to the club and lack of middle-class job skills keep him from walking away. After Clay cedes the presidency to him, he tries to move Sons out of gunrunning and into pornography, a less violent business, but various forces work against against him. Tenuous alliances with other gangs and with the IRA suppliers depend on the continued arms trade. Feuds with other gangs and various federal investigations require his immediate attention. And both Gemma and Clay want things to remain as they are.

The series follows the exploits of Jack Bauer (Kiefer Sutherland), a former Special Forces guy working on and off for a government agency called the Counter-Terrorist Unit. Season after season he saves America from deadly terrorist threats in a world where the terrorists are all masterminds and the government functionaries who combat them are — with the exception of Jack and a few others — incompetent or corrupt. At first he comes off as such a straight arrow that more than one bad guy refers to him sneeringly as a Boy Scout.

The series follows the exploits of Jack Bauer (Kiefer Sutherland), a former Special Forces guy working on and off for a government agency called the Counter-Terrorist Unit. Season after season he saves America from deadly terrorist threats in a world where the terrorists are all masterminds and the government functionaries who combat them are — with the exception of Jack and a few others — incompetent or corrupt. At first he comes off as such a straight arrow that more than one bad guy refers to him sneeringly as a Boy Scout. Jack Bauer tortures suspects to obtain information despite the unreliability of torture as an interrogation technique. Even in the world of 24, it often fails to yield results. Jack himself is tortured repeatedly but never gives up information, not even during the nineteen months he spends in a Chinese prison camp. Some of the terrorists are equally tough. Yet the good guys and bad guys torture their enemies routinely because, what the hell, now and then it works. And Jack is always Running Out of Time and compelled to Do Whatever It Takes. In Season 6 he ends up in front of a Senate subcommittee investigating the illegal use of torture by the government — until the FBI borrows him to help fend off yet another terrorist threat and he interrogates a suspect with the help of a stun gun.

Jack Bauer tortures suspects to obtain information despite the unreliability of torture as an interrogation technique. Even in the world of 24, it often fails to yield results. Jack himself is tortured repeatedly but never gives up information, not even during the nineteen months he spends in a Chinese prison camp. Some of the terrorists are equally tough. Yet the good guys and bad guys torture their enemies routinely because, what the hell, now and then it works. And Jack is always Running Out of Time and compelled to Do Whatever It Takes. In Season 6 he ends up in front of a Senate subcommittee investigating the illegal use of torture by the government — until the FBI borrows him to help fend off yet another terrorist threat and he interrogates a suspect with the help of a stun gun. Despite his violent ways, I can’t help liking Jack Bauer. He’s an idealist willing to give his life, if necessary, to complete his Mission. The US government doesn’t bother rescuing him from the Chinese prison camp until a terrorist offers vital information in exchange for him. (He once tortured the terrorist’s brother to death and understandably the man wants payback.) Jack is okay with being tortured to death in a good cause. “It would be a relief,” he says. This is so sad that I can’t help feeling for him.

Despite his violent ways, I can’t help liking Jack Bauer. He’s an idealist willing to give his life, if necessary, to complete his Mission. The US government doesn’t bother rescuing him from the Chinese prison camp until a terrorist offers vital information in exchange for him. (He once tortured the terrorist’s brother to death and understandably the man wants payback.) Jack is okay with being tortured to death in a good cause. “It would be a relief,” he says. This is so sad that I can’t help feeling for him. So he battles his way through season after season, emptying countless clips of ammo into bad guys, becoming increasingly grizzled and stoic and lonely. His occasional private tears show that he understands how much his work is eroding his humanity. In the final season, I keep hoping he can retire at last and spend time with his granddaughter. Instead he meets a predictable unhappy fate. He gives himself up to the Russians to save the one friend he has left.

So he battles his way through season after season, emptying countless clips of ammo into bad guys, becoming increasingly grizzled and stoic and lonely. His occasional private tears show that he understands how much his work is eroding his humanity. In the final season, I keep hoping he can retire at last and spend time with his granddaughter. Instead he meets a predictable unhappy fate. He gives himself up to the Russians to save the one friend he has left.