The image remains among the most vivid of my early childhood. My three-year-old brother Steve stood in front of our house in Soldiers Summit, wearing one of my dresses as punishment for—something. I don’t recall much about the dress, just a general impression of frills. I’m pretty sure the dress had a sash that tied in a bow in back.

But I recall my brother’s face vividly, wet with tears, screwed up in anger, bright red with humiliation.

I carried the memory for several years without knowing how Steve ended up in the dress. I couldn’t ask him about a punishment so humiliating. He’d probably been too young to remember it anyway.

When I was twelve or thirteen, I asked Nana, my paternal grandmother, about the dress. She’d been living with us at the time. She said my mother put him in the dress and sent him outside to punish him for wetting the bed. I didn’t challenge this story—Nana wasn’t someone easily challenged—but I harbored doubts. Although Mom could become emotionally abusive when angry, this sort of cruel punishment seemed unlike her.

Many years later, when Mom was in her 80s, I told her about my memory of Steve wearing my dress and crying. I didn’t mention that Nana had blamed her. Mom remembered the incident. She said Nana had punished Steve for wetting the bed. Nana put the dress on him and made him go outside until Dad came home.

“I never saw your dad so angry,” Mom said. “He told Mabel to get that damn dress off Steve. He said he’d throw her out of the house if she ever pulled something like that again.” Mom still blamed herself. “He was my child and I should’ve protected him. I was afraid to stand up to Mabel.”

I believed my mother. It seemed likely that Nana would impose that kind of punishment. She’d grown up poor in the South and never finished fourth grade. She probably hadn’t known any better. But later she knew, and felt ashamed enough to lie about it.

I wonder about the effect of the punishment on Steve. He grew up around people who despised feminine traits in men. He became a man who felt compelled to answer any challenge to his masculinity with violence.

Once, while I was walking on a Salt Lake street with Steve and his second wife, a guy we passed said something. I didn’t hear the remark, but it sparked instant rage in Steve. He wanted to fight. His wife and I managed to calm him down and keep him walking. “Why bother with assholes like that?” I asked.

“You’re a girl,” he said. “You don’t know what it’s like, having to prove yourself all the time.”

I did have to prove myself, only not in the same ways, but arguing with him would have made things worse.

In his late twenties Steve worked in oil exploration, an outdoors job that made him physically strong. In his thirties he lifted weights to maintain his fitness. He was big and formidable, the kind of man who could and did mete out punishment to anyone who messed with him. With me and others he loved, he could be kind, generous, and forgiving. But that softness had to be armored, always.

In his late twenties Steve worked in oil exploration, an outdoors job that made him physically strong. In his thirties he lifted weights to maintain his fitness. He was big and formidable, the kind of man who could and did mete out punishment to anyone who messed with him. With me and others he loved, he could be kind, generous, and forgiving. But that softness had to be armored, always.

Steve died of a drug overdose when he was thirty-seven years old.

While sunny Olympus endures forever, snowy Asgard lives in the shadow of Ragnorok, the death of the gods and the destruction of the world. Having lived through my parents’ violent divorce, I could imagine an inevitable and cataclysmic battle that destroys the world.

While sunny Olympus endures forever, snowy Asgard lives in the shadow of Ragnorok, the death of the gods and the destruction of the world. Having lived through my parents’ violent divorce, I could imagine an inevitable and cataclysmic battle that destroys the world. Of all the characters in Norse mythology, my favorite was Loki, the trickster.

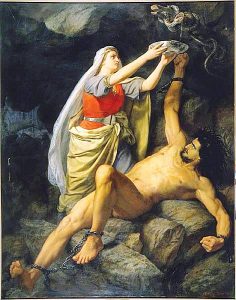

Of all the characters in Norse mythology, my favorite was Loki, the trickster. I forgot the dark conclusion of Loki’s story, perhaps because I liked him so much. In the end, his envy and malice overwhelm fear of punishment. He contrives the death of the god Baldr. For that crime he’s doomed to suffer torment, bound in a cave while poisonous serpent’s venom drips on him, until the coming Ragnorok frees him to fight with the armies of darkness.

I forgot the dark conclusion of Loki’s story, perhaps because I liked him so much. In the end, his envy and malice overwhelm fear of punishment. He contrives the death of the god Baldr. For that crime he’s doomed to suffer torment, bound in a cave while poisonous serpent’s venom drips on him, until the coming Ragnorok frees him to fight with the armies of darkness.

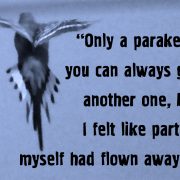

His vocabulary included such staples as “Benji is a pretty bird” and “Hey baby, you’re cute.” He might have learned more if I’d had the patience to teach him. But I would have loved him whether he talked or not. Gentle and affectionate, he liked perching on my shoulder and nibbling my ear as I read or watched TV. He soon began joining me at meals where — to Joe’s disgust — he perched on the rim of my plate and nibbled my food. He especially liked spaghetti in tomato sauce.

His vocabulary included such staples as “Benji is a pretty bird” and “Hey baby, you’re cute.” He might have learned more if I’d had the patience to teach him. But I would have loved him whether he talked or not. Gentle and affectionate, he liked perching on my shoulder and nibbling my ear as I read or watched TV. He soon began joining me at meals where — to Joe’s disgust — he perched on the rim of my plate and nibbled my food. He especially liked spaghetti in tomato sauce.