I was half asleep when my husband put on one of my favorite CDs, Nude and Rude: The Best of Iggy Pop. You might figure the aural assault of “Search and Destroy” or the pounding beat of “Lust for Life” would wake me up, but I drowsed through both songs. It was Iggy’s haunting and poetic “The Passenger” that brought me to life.

Here let me explain that I’m one of those annoying people who play the same song over and over and over until you want to grab a baseball bat and pound their music-playing equipment into rubble. (Anyone who roomed near me in college, please accept my belated apology.) This mental disorder has somewhat abated now that I’m old, but “The Passenger” is a song I used to play 28 times in a row. I feel a deep psychic connection to this dark song about riding without end through the city at night.

The first stanza goes:

I am the passenger

And I ride and I ride

I ride through the city’s backside

I see the stars come out of the sky

Yeah, they’re bright in a hollow sky

You know it looks so good tonight

I am the passenger

I stay under glass

I look through my window so bright

I see the stars come out tonight

I see the bright and hollow sky

Over the city’s a rip in the sky

And everything looks good tonight

You don’t know who’s driving the passenger’s car.” A chauffeur? Anyway, the passenger seems unworried about being taken where he doesn’t want to go. Nor is he concerned about danger. “The city’s ripped backside” suggests the bad side of town—vacant buildings, broken windows, vacant and broken people. But he isn’t brushing against any of this damage. He remains “under glass” like something rare and protected, safe behind his window.

“The Passenger” has three stanzas. In the first one the singer is the passenger, but in the second he invites listeners to come along for the ride. “Get in the car,” he says. “We’ll be the passenger.” And in the third stanza the passenger becomes a third-person entity. He has morphed from a person to a way of being in the world.

Under glass, looking through his “window’s eye,” the passenger is the center of the universe. Nothing touches him, and everything he looks upon is his. He says, “All of it was made for you and me. / Come take a ride and see what’s mine.” The purpose of the ride is to see, and in the act of seeing, to possess—not just the city but “the bright and hollow sky” and all the stars in it.

The world belongs to him entirely.

But his ownership comes with a curse. He can see but not touch. If he leaves the car and steps out in the world, it no longer belongs to him. Whatever he touches will touch him right back. No control. No protection from pain or damage. The passenger has to keep moving and stay encapsulated. The song is haunting because nothing belongs to him really. Everything happens in his head, and that’s enough. The music will carry him anywhere he wants to go. He moves through the world like a ghost.

The endlessness of his ride is expressed in the obsessive rhythm of the music and the repetition of the same imagery with slight permutations from stanza to stanza. The passenger “rides and rides and rides” and goes nowhere. These qualities make the song a perfect choice for playing over and over. And my emotional response is simple: Take me for that ride.

It’s easy to look at Iggy Pop’s career and stage persona and conclude “The Passenger” is about heroin, which is both obvious and beside the point. I listen to the song and feel the perilous allure of disengaging from the world. And I don’t have to shoot smack to disengage. I can go crazy or join a bizarre cult or spend every waking hour surfing the Web — or just refuse to wake up in the morning.

When “The Passenger” played, I rolled out of bed and danced until the music ended. Then I sat down to write.

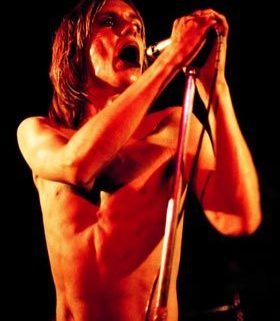

Photo from fanpop.com

Very thought provoking, Mary. I am especially drawn to your observation, “But his ownership comes with a curse. He can see but not touch. If he leaves the car and steps out in the world, it no longer belongs to him. Whatever he touches will touch him right back. No control.”

This captures exactly how I feel about publishing. As long as a story is mine alone, I have control of the story, of what chords the story strikes, and of what affects my illusions, but as soon as I hit that “publish” key, the story is no longer mine alone. I can no longer protect it, or control what touches it. And it’s nearly impossible to “get back in the car.”

Thank you for the insightful explication. My mind needed a little morning workout, and you provided it. Have a great day!

Thanks for stopping by to read, Ricki. You’re right that published work no longer belongs entirely to the writer. But writers still feels hurt when their books are harshly treated.