Imagine being wrongly accused, arrested and jailed for a crime you didn’t commit. Everyone—your colleagues, your friends, maybe even your life partner—assumes you must be guilty. After all, the police wouldn’t arrest you without solid evidence. Recently I read two thrillers based on this nightmarish scenario. The protagonists of both Rachel Caine’s Stillhouse Lake and Candice Fox’s Crimson Lake find themselves wrongly accused of heinous crimes.

Readers identify with a wrongly accused protagonist because the injustice appalls them—usually. They may lose their sympathy for a stupid or morally compromised character. Most of us harbor a deep fear of finding ourselves in a similar situation. It only takes bad luck—being in the wrong place at the wrong time or being targeted by a vindictive enemy—to place us in the crosshairs of the justice system. But when a character acts foolishly or has an unsavory side, we’re liable to back away. Not me, we think. I’d never be like that or do such an idiotic thing.

A naive woman wrongly accused of her husband’s crimes

In Stillhouse Lake, Gina Royal begins as a “normal” if overly docile housewife married to a man who’s oddly territorial about the garage, which he has converted into his personal workshop and keeps locked at all times. The reason for his secretive behavior becomes obvious when a driver loses control of her car and plows into the garage. The accident uncovers the hanging corpse of a woman, naked and showing obvious signs of torture.

In Stillhouse Lake, Gina Royal begins as a “normal” if overly docile housewife married to a man who’s oddly territorial about the garage, which he has converted into his personal workshop and keeps locked at all times. The reason for his secretive behavior becomes obvious when a driver loses control of her car and plows into the garage. The accident uncovers the hanging corpse of a woman, naked and showing obvious signs of torture.

Poor Gina stayed married for years to a serial killer without suspecting the truth. The police don’t buy her protestations of innocence. Her husband tortured women in the garage next to her kitchen. How can she be innocent? Either she participated, or at least helped cover up the crimes, or she’s hopelessly stupid—all reasons for withholding sympathy. Yet the author persuades me that Gina is wrongly accused. She became her husband’s doormat because she wanted to believe she had a storybook marriage. Many of us practice this sort of denial to the keep unbearable truths about our lives at bay.

Although a jury finds Gina not guilty, the families of her husband’s victims gin up an online mob to hound her. They find and dox her no matter where she goes or how many times she changes her name. They seem unbothered that her two children also suffer from the harassment. By the time she moves into a comfortable old house near Stillhouse Lake, she has changed her name to Gwen Proctor and is nobody’s shrinking violet anymore. She can never prove her innocence or clear her name, but she fights to protect her children and reclaim her life. She goes on fighting in subsequent books of the Stillhouse Lake series. In the end her grit earns my sympathy and admiration.

A cop ensnared by circumstance and wrongly accused of rape

In Crimson Lake, Ted Conkaffey has a respectable life as a police officer in Sydney, Australia until he faces trial for raping a little girl. His colleagues and friends abandon him and his wife soon follows. His prosecution gets put on hold for lack of evidence, leaving the terrible accusation hanging over him. Thanks to publicity about the case, the entire nation despises Ted. He flees to the remote area of Crimson Lake, seeking anonymity, but the locals discover who he is and begin a campaign of harassment against him.

In Crimson Lake, Ted Conkaffey has a respectable life as a police officer in Sydney, Australia until he faces trial for raping a little girl. His colleagues and friends abandon him and his wife soon follows. His prosecution gets put on hold for lack of evidence, leaving the terrible accusation hanging over him. Thanks to publicity about the case, the entire nation despises Ted. He flees to the remote area of Crimson Lake, seeking anonymity, but the locals discover who he is and begin a campaign of harassment against him.

Ted tells his own story, but some first-person narrators are unreliable. Could Ted be lying? His alibi makes sense even though he can’t prove it, but one detail persuades me that he’s innocent. Near the beginning of the story he rescues a family of geese and pays a ridiculously high vet bill to save the wounded mother. Okay, I’m sentimental about animals, but it seems unlikely that a character who rescues and adopts a family of geese would rape a child. Or anyone for that matter.

To prove his innocence and regain his reputation, Ted must track down the man who raped the little girl. He’s still searching when Crimson Lake ends. His story continues in Redemption Point, the next book of the series.

A woman wrongly accused of provoking her boyfriend to murder

It intrigues me the way innocent people get blamed for things they never did. They make bad choices like Gina Royal or they’re in the wrong place at the wrong time like Ted Conkaffey.

Kelly Durrell, the protagonist of my novel Hometown Boys, takes the blame after her long-ago ex-boyfriend murders her aunt and uncle. She might not be a criminal, but she’s held morally responsible. Gossip against her spreads through her hometown, fueled by some townspeople’s dislike of her and the expedience of a few others. Like Gina, she made a mistake. She dated the killer in high school. The gossipers don’t care that she’s changed in the two decade since then. Like Ted Conkaffey, she must find out the truth to clear her name—to the extent it can be cleared.

Someone wrongly accused of a crime or even a peccadillo can never be altogether innocent again.

Thriller fans will enjoy Crimson Lake and Stillhouse Lake. And since both are the first book of a series, readers can keep the thrill ride going.

While sunny Olympus endures forever, snowy Asgard lives in the shadow of Ragnorok, the death of the gods and the destruction of the world. Having lived through my parents’ violent divorce, I could imagine an inevitable and cataclysmic battle that destroys the world.

While sunny Olympus endures forever, snowy Asgard lives in the shadow of Ragnorok, the death of the gods and the destruction of the world. Having lived through my parents’ violent divorce, I could imagine an inevitable and cataclysmic battle that destroys the world. Of all the characters in Norse mythology, my favorite was Loki, the trickster.

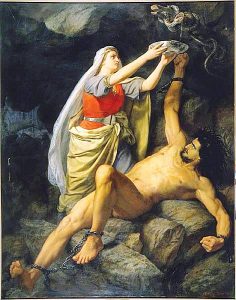

Of all the characters in Norse mythology, my favorite was Loki, the trickster. I forgot the dark conclusion of Loki’s story, perhaps because I liked him so much. In the end, his envy and malice overwhelm fear of punishment. He contrives the death of the god Baldr. For that crime he’s doomed to suffer torment, bound in a cave while poisonous serpent’s venom drips on him, until the coming Ragnorok frees him to fight with the armies of darkness.

I forgot the dark conclusion of Loki’s story, perhaps because I liked him so much. In the end, his envy and malice overwhelm fear of punishment. He contrives the death of the god Baldr. For that crime he’s doomed to suffer torment, bound in a cave while poisonous serpent’s venom drips on him, until the coming Ragnorok frees him to fight with the armies of darkness.