The day I returned to work after my brother’s funeral, one of my former students, ‘Trevor’, dropped by to announce that his world had collapsed. His fiancée had dumped him for some guy with lots of money. He was going to drop out of graduate school and he didn’t give a shit what happened him anymore. I assumed, mistakenly, that Trevor wanted me to talk him out of his despair. I’ve never been much good at that kind of thing, but I gave it a shot.

He might see things differently in a few months, I pointed out. Why not finish the semester? Then he could take the summer to decide what he wanted to do.

No way, Trevor said. He was too devastated to go on.

I told him my brother had just died and I was still in shock, but I was teaching my classes. Not functioning at full capacity, maybe, but trying. I doubted it would ease my grief to sit around thinking about how much I missed my brother. It would probably make things worse.

“Sorry about your brother,” Trevor said, and then he added, “Well, at least your brother didn’t reject you.”

From Trevor’s perspective, his grief was more severe than mine because his fiancée’s desertion left him feeling worthless. Yet in ten years — if he didn’t kill himself or become a hopeless drunk — he might meet another woman, someone kinder and more deserving of his love. But no one could replace my brother.

None of us fully understands someone else’s pain or grief. We only imagine it based on our own experience. Although boyfriends have dumped me, none of them mattered as much as Trevor’s fiancée mattered to him. And supposing Trevor had a sibling who died, the two of them might not have been as fiercely close as my brother and I were.

The loss of anyone leaves a hole in your life, and the depth of your grief is roughly proportionate to the size of that hole. What did you share with the one who’s gone? How much of yourself did you give? Nobody knows that but you.

All of this brings me to Westie, my parakeet, who died on Christmas Eve. To many people the loss of a pet is unimportant, especially a small bird. But Westie meant a lot to me. I talked and sang to him every evening before I put him to bed. My husband talked and whistled to him every morning. As a result he knew quite a few words and chattered and sang to us every day until he fell ill. Some of his favorites were “Won’t you kiss me?” and “Smile when you say that,” and “That’s Mr. Westie to you.” He whistled the opening notes of “The Star-Spangled Banner” and “Ride of the Valkyrie” and several other tunes.

He spent his last day snuggled against my chest while I wrote and read and watched videos on my iPad. That night I dozed in a recliner with Westie cupped in my hands. At four in the morning he fluttered away from me. I picked him up and he tried again to fly away. He wanted me to let him go. I placed him in his cage, where he died a few minutes later.

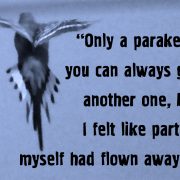

Only a parakeet, you can always get another one, but I felt like part of myself had flown away.

The loss of Westie is a small grief, but it hurts.

(The quotation is taken from Daemon Seer whren Lu’s parakeet, Foster, is bird-napped by daemons.)

Jax finds himself torn between his father’s idealism, as revealed in the journal he left, and the hard pragmatism and ambition of Clay and Gemma. His ambivalence about the club’s criminal enterprises drives much of the conflict within the family. There are echoes of Hamlet, with Jax as the brooding son and Clay as the uncle who has taken his dead brother’s wife. Gemma, however, is no foolish Queen Gertrude. She’s more like Lady Macbeth without the guilt.

Jax finds himself torn between his father’s idealism, as revealed in the journal he left, and the hard pragmatism and ambition of Clay and Gemma. His ambivalence about the club’s criminal enterprises drives much of the conflict within the family. There are echoes of Hamlet, with Jax as the brooding son and Clay as the uncle who has taken his dead brother’s wife. Gemma, however, is no foolish Queen Gertrude. She’s more like Lady Macbeth without the guilt. When Jax marries his childhood sweetheart, Tara (Maggie Siff), Gemma’s connection to her son is threatened. A skilled surgeon, Tara stitches up the Sons’ gunshot wounds and learns to shoot a gun, but she doesn’t want the outlaw life for their children. She urges Jax to abandon the Sons. He also wants something better, but his loyalty to the club and lack of middle-class job skills keep him from walking away. After Clay cedes the presidency to him, he tries to move Sons out of gunrunning and into pornography, a less violent business, but various forces work against against him. Tenuous alliances with other gangs and with the IRA suppliers depend on the continued arms trade. Feuds with other gangs and various federal investigations require his immediate attention. And both Gemma and Clay want things to remain as they are.

When Jax marries his childhood sweetheart, Tara (Maggie Siff), Gemma’s connection to her son is threatened. A skilled surgeon, Tara stitches up the Sons’ gunshot wounds and learns to shoot a gun, but she doesn’t want the outlaw life for their children. She urges Jax to abandon the Sons. He also wants something better, but his loyalty to the club and lack of middle-class job skills keep him from walking away. After Clay cedes the presidency to him, he tries to move Sons out of gunrunning and into pornography, a less violent business, but various forces work against against him. Tenuous alliances with other gangs and with the IRA suppliers depend on the continued arms trade. Feuds with other gangs and various federal investigations require his immediate attention. And both Gemma and Clay want things to remain as they are.

The series follows the exploits of Jack Bauer (Kiefer Sutherland), a former Special Forces guy working on and off for a government agency called the Counter-Terrorist Unit. Season after season he saves America from deadly terrorist threats in a world where the terrorists are all masterminds and the government functionaries who combat them are — with the exception of Jack and a few others — incompetent or corrupt. At first he comes off as such a straight arrow that more than one bad guy refers to him sneeringly as a Boy Scout.

The series follows the exploits of Jack Bauer (Kiefer Sutherland), a former Special Forces guy working on and off for a government agency called the Counter-Terrorist Unit. Season after season he saves America from deadly terrorist threats in a world where the terrorists are all masterminds and the government functionaries who combat them are — with the exception of Jack and a few others — incompetent or corrupt. At first he comes off as such a straight arrow that more than one bad guy refers to him sneeringly as a Boy Scout. Jack Bauer tortures suspects to obtain information despite the unreliability of torture as an interrogation technique. Even in the world of 24, it often fails to yield results. Jack himself is tortured repeatedly but never gives up information, not even during the nineteen months he spends in a Chinese prison camp. Some of the terrorists are equally tough. Yet the good guys and bad guys torture their enemies routinely because, what the hell, now and then it works. And Jack is always Running Out of Time and compelled to Do Whatever It Takes. In Season 6 he ends up in front of a Senate subcommittee investigating the illegal use of torture by the government — until the FBI borrows him to help fend off yet another terrorist threat and he interrogates a suspect with the help of a stun gun.

Jack Bauer tortures suspects to obtain information despite the unreliability of torture as an interrogation technique. Even in the world of 24, it often fails to yield results. Jack himself is tortured repeatedly but never gives up information, not even during the nineteen months he spends in a Chinese prison camp. Some of the terrorists are equally tough. Yet the good guys and bad guys torture their enemies routinely because, what the hell, now and then it works. And Jack is always Running Out of Time and compelled to Do Whatever It Takes. In Season 6 he ends up in front of a Senate subcommittee investigating the illegal use of torture by the government — until the FBI borrows him to help fend off yet another terrorist threat and he interrogates a suspect with the help of a stun gun. Despite his violent ways, I can’t help liking Jack Bauer. He’s an idealist willing to give his life, if necessary, to complete his Mission. The US government doesn’t bother rescuing him from the Chinese prison camp until a terrorist offers vital information in exchange for him. (He once tortured the terrorist’s brother to death and understandably the man wants payback.) Jack is okay with being tortured to death in a good cause. “It would be a relief,” he says. This is so sad that I can’t help feeling for him.

Despite his violent ways, I can’t help liking Jack Bauer. He’s an idealist willing to give his life, if necessary, to complete his Mission. The US government doesn’t bother rescuing him from the Chinese prison camp until a terrorist offers vital information in exchange for him. (He once tortured the terrorist’s brother to death and understandably the man wants payback.) Jack is okay with being tortured to death in a good cause. “It would be a relief,” he says. This is so sad that I can’t help feeling for him. So he battles his way through season after season, emptying countless clips of ammo into bad guys, becoming increasingly grizzled and stoic and lonely. His occasional private tears show that he understands how much his work is eroding his humanity. In the final season, I keep hoping he can retire at last and spend time with his granddaughter. Instead he meets a predictable unhappy fate. He gives himself up to the Russians to save the one friend he has left.

So he battles his way through season after season, emptying countless clips of ammo into bad guys, becoming increasingly grizzled and stoic and lonely. His occasional private tears show that he understands how much his work is eroding his humanity. In the final season, I keep hoping he can retire at last and spend time with his granddaughter. Instead he meets a predictable unhappy fate. He gives himself up to the Russians to save the one friend he has left.