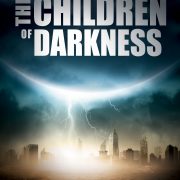

It’s finally here! Children of Darkness – Book One in The Seekers Series is available NOW. Check it out on Amazon.com. FREE for Kindle Unlimited subscribers. GET YOUR COPY

“A must-read page turner.” Kirkus Review

About the Book:

The Children of Darkness is about a society devoid of technology, the result of an overreaction to a distant past where progress had overtaken humanity and led to social collapse. The solution—an enforced return to a simpler time. But Children is also a coming of age story, a tale of three friends and their loyalty to each other as they struggle to confront a world gone awry. Each searches for the courage to fight the limits imposed by their leaders, along the way discovering their unique talents and purpose in life.

“If the whole world falls into a Dark Age, which it could plausibly do, who could bring us out of it? According to David Litwack in The Children of Darkness, the only answer is us, now, somehow reaching into the future.” – Kaben Nanlohy for On Starships And Dragonwings

Publication Date: June 22, 2015 from Evolved Publishing

Purchase Link: http://smarturl.it/

FREE WITH KINDLE UNLIMITED

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/23485495-the-children-of-darkness

Book Description

The Children of Darkness, book one of the dystopian trilogy, The Seekers

“But what are we without dreams?”

A thousand years ago the Darkness came–a time of violence and social collapse when technology ran rampant. But the vicars of the Temple of Light brought peace, ushering in an era of blessed simplicity. For ten centuries they have kept the madness at bay with “temple magic,” eliminating forever the rush of progress that nearly caused the destruction of everything.

Childhood friends, Orah and Nathaniel, have always lived in the tiny village of Little Pond, longing for more from life but unwilling to challenge the rigid status quo. When their friend Thomas returns from the Temple after his “teaching”—the secret coming-of-age ritual that binds the young to the Light—they barely recognize the broken and brooding man the boy has become. Then when Orah is summoned as well, Nathaniel follows in a foolhardy attempt to save her.

In the prisons of Temple City, they discover a terrible secret that launches the three on a journey to find the forbidden keep, placing their lives in jeopardy. For hidden in the keep awaits a truth from the past that threatens the foundation of the Temple. If they reveal that truth, they might release the long-suppressed potential of their people, but they would also incur the Temple’s wrath as it is written:

“If there comes among you a dreamer of dreams saying ‘Let us return to the darkness,’ you shall stone him, because he has sought to thrust you away from the light.”

“A fresh perspective on our own society…[an] enjoyable read that will make you wonder just how society will judge us in the future.” Lexie

About the Author:

The urge to write first struck when working on a newsletter at a youth encampment in the woods of northern Maine. It may have been the night when lightning flashed at sunset followed by northern lights rippling after dark. Or maybe it was the newsletter’s editor, a girl with eyes the color of the ocean. But he was inspired to write about the blurry line between reality and the fantastic.

The urge to write first struck when working on a newsletter at a youth encampment in the woods of northern Maine. It may have been the night when lightning flashed at sunset followed by northern lights rippling after dark. Or maybe it was the newsletter’s editor, a girl with eyes the color of the ocean. But he was inspired to write about the blurry line between reality and the fantastic.

Using two fingers and lots of white-out, he religiously typed five pages a day throughout college and well into his twenties. Then life intervened. He paused to raise two sons and pursue a career, in the process becoming a well-known entrepreneur in the software industry, founding several successful companies. When he found time again to daydream, the urge to write returned.

After publishing two award winning novels, Along the Watchtower and The Daughter of the Sea and the Sky, he’s hard at work on the dystopian trilogy, The Seekers.

David and his wife split their time between Cape Cod, Florida and anywhere else that catches their fancy. He no longer limits himself to five pages a day and is thankful every keystroke for the invention of the word processor.

Website: www.davidlitwack.com

Facebook: David Litwack – Author

Twitter: @DavidLitwack

Giveaway

a Rafflecopter giveaway

More Reviews!

“Litwack’s storytelling painted a world of both light and darkness–and the truth that would mix the two.” Fiction Fervor

“The Children of Darkness is a dystopian novel that will stay with you long after you finish reading it.” C.P. Bialois

“This is a satisfying exploration of three teens’ journey into the unknown, and the struggles faced by all who seek true emancipation – both for themselves, and for the people they love.” Suzy Wilson

“Litwack’s writing is fresh, and Nathaniel, Orah and Thomas come to life in your imagination as you frantically flip (or click) the pages of this book.” Anna Tan

“…many profound themes, lovely characterizations and relationships” R. Campbell

“I was enthralled and intrigued by the authors creation of this society… David Litwack has an enjoyable and captivating writing style.” Jill Marie

“…a perfect story for young adult readers, but its underlying theme and character development will keep any adult engaged.” Kathleen Sullivan

Get Your Copy Now!

Get Your Copy Now!