My brother’s birthday is coming up, but he won’t be around to celebrate it. He died of a heroin overdose in 1987. Here’s what I have left of him: The hardhat he wore as an oil exploration worker. The old trunk, plastered with decals, that held his clothes and books when he traveled. Old photographs. And of course my memories. Some of the photographs are inherited from my grandmother. On the back of each one she diligently noted the date it was taken and who was in the shot. I’m grateful to her for that. Sometimes I can’t recognize faces from long ago. Looking at them makes me sad. Steve died young. Life wasn’t always kind to him, and he wasn’t always kind to himself. The photos show how he grew. And changed. They stir memories that have been submerged a long time.

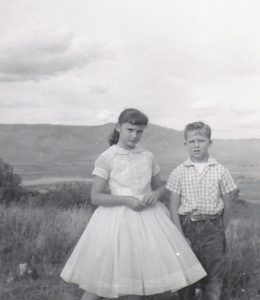

I don’t remember where or when this picture of Steve and me was taken. It looks like an airfield. Those are the Wasatch Mountains in the background. Steve and I used to make up stories for hours on end, speaking in the voices of the characters we imagined. Maybe that’s why I rely so much on dialogue in my fiction.

This one with me in the ridiculous dress was taken on Easter. Every year on Easter Sunday we went with Mom and Grandma to an all-you-can eat buffet, always the same one. Steve loved their pie. One year we noticed the restaurant had raised the price for children and blamed the increase on Steve. But I’ve attached that sweet memory to the wrong picture. We’re too young here. The buffet came later.

Here is Steve with Grandma. He was in high school then. Since he lived with Dad and I lived with Mom, we only saw each other on holidays and during summer vacations.

He was a party animal who could down a six-pack faster than anybody. His favorite novel was Crime and Punishment. He got straight and stayed that way for a year or so before he relapsed.

Steve and I lived a thousand miles apart and seldom saw each other as adults. But when we did, things were the same as they always had been. He never stopped being my brother.